Behind the Ivy - a story of a Methodist Chapel

- DCHP

- Feb 2, 2021

- 15 min read

Updated: Feb 18, 2021

For decades a small cottage with two arched windows and an eye-catching bright green porch has sat silently as ivy continues to overtake it, hiding the long and fascinating history of the Methodist Church or Chapel on Cheapside Lane. We can reveal it.

Origins

There are mysteries about the origins of the Methodist Chapel building and a little detective work is needed.

There is a map of the Parish of Denham as it was in 1783. It shows a row of cottages near the intersection of Village Road and Cheapside, later renamed Cheapside Lane. Further to the south a small row of buildings is shown just on the corner of Ashmead Lane and Cheapside. That may have included the building which later became the Chapel, but the marking is small and not consistent with a later slightly larger map of 1843, the Tithe Map.

The word “tithe” was used to describe a form of taxation of agricultural property by which one tenth of the land’s produce was applied for the benefit of the established church. An Act of 1836 turned it into a charge payable in money and it then became necessary to assess how much each property holder should pay. This involved the production of a map of each English or Welsh parish or township, together with an accompanying schedule giving the names of all owners and occupiers of land in the parish. The tithe agreement or award formed the basis of the tithe apportionment, which was the legal document setting out each landowners' individual liabilities. Both the map and the apportionment were signed by the Tithe Commissioners.

Denham's Tithe Map and Award from 1843 has survived. It shows the overall area including what may be the chapel although, since it was not an occupied dwelling, it wasn't specifically named on the map nor in the award. The row of cottages on Cheapside Lane were given lot numbers from 374-377 and their owners and occupiers were identified.

This is what the record shows:

Plot 374 was owned by Robert House and was two tenements & gardens occupied by a Chas Hitch and Thos Edwards.

Plot 374a was owned by Richard Bolton, it was also two tenements & gardens and was occupied by John House and William Platt

Plot 375 was owned by Sarah House and were cottages and gardens occupied by Jonathan Staines, David West & John Simms

Plot 375a was owned by Thomas Brown and was a cottage and garden occupied by Thomas Judge

Plot 376 a house and plot 377 a wheeler's shop and yard were owned by Thomas Elton and occupied by Robert House

Plot 377a was owned (and occupied) by the "British School Trustees".

In 2008 South Bucks District Council carried out the "Denham Conservation Area Character Appraisal". It describes the Methodist Chapel as "the sole survivor of a row of cottages shown on the 1783 parish map" and continues:

"The adjoining cottages were demolished in 1940. Said to have been built by Mr. House. In c.1828 the house of John House, wheelwright, was registered for Wesleyans, although the plaque on the building states “Wesleyan Chapel 1820”. There is evidence of altered openings so the cottage is presumed to have been converted into a chapel around 1820."

Can more be found ? We can see from the Tithe Awards that several members of the House Family were living in those cottages. With a well conveniently located at the intersection with Ashmead Lane, John House lived there with his family and operated a wheelwright business out of the row of cottages.

Wheelwrights

Wheelwrights were clearly craftsmen of a high order who passed on the acquired knowledge of their craft from father to son, from master to apprentice. They created patterns for wagon wheels, for dung cart wheels, and for raved cart wheels. Raves were side rails added to a cart or wagon to allow a bigger load to be carried over the wheels. Eventually, the all-wooden hubs, spokes and wheels were reinforced with iron strakes, lengths of iron that were nailed to the outside of wheels to hold wooden wheels together. With the help of a blacksmith, iron hubs as well as metal-banded tyres later became commonplace.

This plate published in a volume of Encyclopédie in 1769 shows both methods of shoeing a wheel. In the centre the labourers are using hammers and "devil's claws" to fit a hoop onto the felloe, and on the right they're hammering strakes into place.

A typical wheelwright's shop of the 17th Century would have comprised a Master Wheelwright, who would be a member of the Worshipful Company of Wheelwrights. This was a company operating under a royal charter granted by Charles II on 3rd February 1670. After receiving the Charter, the Wheelwrights Company carried on the work of a former Guild, but the legal status of a Charter enhanced its power and gave it the right to make its own bye-laws and thus govern the operation of the trade. Eventually, the jurisdiction of the Company covered all wheelwrights working within London and later extended far outside its boundaries. It still exists as one of the great livery company charitable institutions of the City of London.

With the master in an early wheelwright business operating under the worshipful company, there would typically have been several journeymen and half a dozen apprentices, but by 1800 things had changed. In 1801 none of the members of the company were practising craftsmen and the trade itself had moved out of the City of London into businesses such as that of John House in Denham.

Though substantial, John House's business does not seem to have been on quite the scale of its London predecessors. It was certainly quite an old family business. Denham’s 1749 parish census records 6 shoemakers, a butcher, clogmaker, broom maker, tailor and one wheelwright who was later identified as John House, evidently of an earlier generation than the John House of 1843. (As is to be seen, John was a forename the family long preserved.) About 50 years later, in 1798, the official survey listed 204 men between the ages of 16 and 60 in Denham, and again one, but only one, wheelwright.

Whether or not the John House of 1843 was a member of the Worshipful Company of Wheelwrights, he was nonetheless a skilled craftsman and would have been a substantial figure in his community. The House family acquires quite a significance in our story.

But there was something strange about the Tithe Awards list of properties and their owners and occupiers. Why would a 19th century craftsman with a substantial business be no more than the occupier of a property of which someone else i.e. Robert Bolton was the owner ? Strange too is that there is no mention of Robert Bolton in the National Census of 1841, though one Margaret Bolton appears there and again in the census of 1851 where she is described as a "pauper" occupying one of the Cheapside Cottages. How is it then that a member of the Bolton family appears in 1843 as a property owner, whilst John House is no more than an occupant and other members of his family are owners

It is known that only 1 in 6 of the Tithe Maps can be guaranteed as accurate and as to the accuracy of the 1841 census, it has a good chance of being accurate at least so far as the House family are concerned since the compiler was John House's brother William. That in itself gives some status to the family since it shows that William House's literacy was trusted by authority at a time when only two out of three men were considered literate.

But should we assume that the identifications of ownership on the Tithe Award list are in error ?

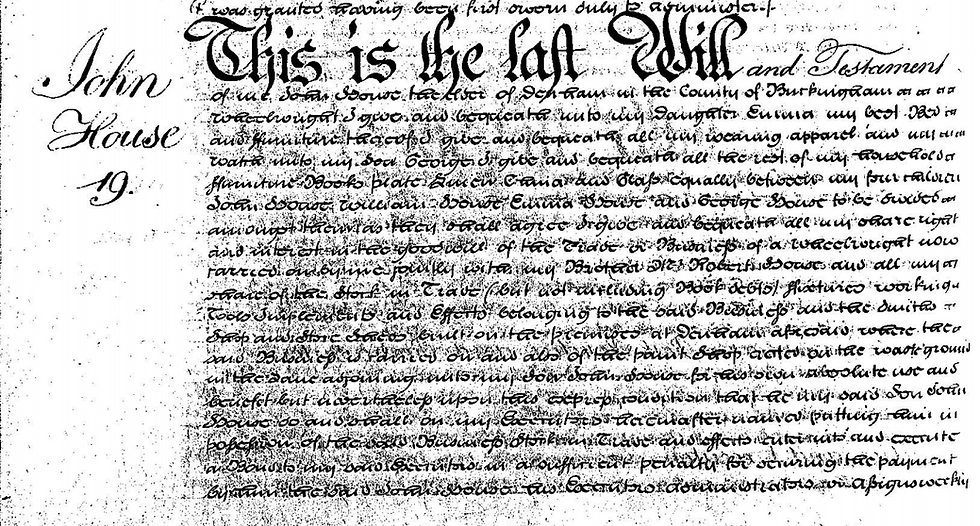

The National Archive at Kew holds the original of the Will of John House of Denham who died in September 1837. It refers to “all of my wheelwright stock in trade now carried on by me jointly with my brother Robert House“. He left all his share in the business to his son, John. This John House junior was evidently the John House mentioned in the Tithe Awards of 1843 and John House senior is evidently the John House mentioned in the South Bucks District Council Character Appraisal in 2008 as the man who registered a property for use as a Wesleyan Chapel. The Will of John House senior clearly gave a very substantial business to John junior but perhaps this did not include a gift of a house other than the right to occupy.

The rest of the Will of John House Senior left no doubt about the chapel. Once the difficult task of deciphering its content is accomplished at least in sufficient part, it is found to contain a direction to his Executors, Edward Fountain and Edward Alport:

... and I give and devise unto the said Edward Fountain and Edward Alport. ..... all that the freehold Building situate in Denham aforesaid .... Wesleyan Methodist Chapel with the appurtenances thereto along with .... said Edward Fountain and Edward Alpert as the sureties (?) of the said George House aforesaid .. and shall as soon as may be after they ......... public sale or private contract make (?) sale and absolutely dispose of the said ... Buildings, hereditaments and premises for the best price that can reasonably be obtained for the same and after the .... to the purchaser or purchasers thereof in such manner as they ... may ... and hereby request my said Trustees to .... the Building aforesaid in the first instance to the body of ... Wesleyan Methodist Denomination but if they decline to purchase ... then to some body of Protestant Deputies (?) of the Independent .......ist Church ...... then I direct my said Trustees to sell ...... willing to ..... the purchase thereof .

That is enough to establish that by 1837, John House senior had established the Wesleyan Methodist Church in property he owned on Cheapside Lane and was directing that it be sold out of his family to the Methodist Church authorities.

But when exactly did John House open up his property for Methodist worship. On a weather-beaten plaque attached to the front of the Chapel building is written “Wesleyan Chapel 1820” but the Denham Conservation Report indicated “c.1828” as the date the house was licensed for the Wesleyans. Another document from 1851 identifies the Wesleyan Chapel, Denham as a place of worship with the year in which it was "erected" (that could be taken as the date of licensing) as 1819.

The rise of Wesleyan Methodism

Historically, there would be good reasons why John House chose to make this substantial contribution to the Methodists, a protestant denomination that was begun in November 1729 by two sons of an Anglican vicar.

James II was the last Roman Catholic monarch of England, Scotland and Ireland. He is now remembered primarily for struggles over religious tolerance and continued wars at home and on the continent. However after he was deposed in 1688 strategies aimed at securing total confessional uniformity were gradually abandoned to bring an end to the conflicts which had caused so much trouble, including civil wars, over the preceding century and a half.

Despite the fact that James II had an infant son, James Francis Edward, who could have succeeded him by hereditary principle, it was Mary his daughter born in 1662 and brought up Protestant, to whom parliament offered the English throne. After her marriage to her Protestant first cousin, William III of Orange, they both ruled as joint sovereigns. This was a tactical move by Parliament who wanted to restrict the succession to a Protestant line, ensuring an end to the idea that the state religion in England could be restored to Roman Catholicism.

The restoration of the monarchy, and with it the established Church of England largely settled religious questions. A Protestant succession was guaranteed in 1689, as was the hegemony of the Anglican Established Church. Persecution had taken its toll and dissenting congregations emerged numerically small and inward looking.

In this new more tolerant environment new religious ideas flourished, many of them endeavouring to bring about religious renewal through persuasive rather than the more coercive state-driven methods of Christianisation that had been customary in the preceding century.

So it was that in 1729 the son of an Anglican clergyman John Wesley went to live and study divinity and classics at Oxford University. He was joined later by his brother Charles a hymn writer, George Whitefield, and John Gambold and others. It was said of these four and the other members of The Holy Club of Oxford that they "systematically and methodically sought to serve God every hour of the day." The description stuck as they evolved the doctrines and practices of Methodism within the Church of England.

Over 50 tumultuous years passed during which John Wesley discovered that only through “field preaching" could he "preach the gospel to every creature” and effect “the change which God works in the heart through faith in Christ.” Later, John Wesley started to preach his vigorous and revivalist message from the pulpit of any Anglican vicar who did not object to his style or message. However, resentment soon flared up, particularly over the large congregations he attracted, and he was banned from preaching in an ever-increasing number of churches.

The size of Wesley's large congregations and the non-availability of pulpits from which to preach to them led to the advent of even more open-air meetings throughout England and Wales. These became a symbol of early Methodism. George Whitefield, a fellow student of the Wesleys at Oxford, became well known for his unorthodox ministry of itinerant open-air preaching. The movement spread, with a significant number of Anglican clergy joining the Methodists in the mid-18th century.

It was common practice in that period to establish "societies" to deal with perceived social ills. Against a background of decadence, and a general decline in religion in favour of lax morals, Wesley set up Societies to seek a deeper holiness of living. Small cell groups were actually known by the Methodists as "Societies" and could vary in size from many hundreds of members subdivided into small bands of 15-20 members.

Preaching served to recruit people to the Society. Only as Societies began to organise themselves as more than a mid-week gathering seeking holiness, and offering worship on Sunday, did the breach with the established Church of England begin to appear. Indeed, Wesley himself wanted to stay within the Anglican Church.[9] Many of the Methodist itinerant clergy were not authorised to administer communion, conduct marriages, baptisms, or funerals, and Wesley felt that he needed to be able to offer these sacraments to his followers.

The Toleration Act 1689 required that dissenter Chapels and preachers must be licensed. Wesley in fact established the first Methodist Chapel in 1739 and at times these chapels were established without compliance with the law but by 1787 he had been forced to license the Chapels under the Toleration Act so effectively defining Methodists dissenters for legal purposes. The spiritual dedication of the Methodists eventually led to a break with the Church of England in 1795, four years after John Wesley's death.

The practice of Methodism

For practising Methodists, the Bible was the foundational text, and the widespread use of biblical imagery and terminology ensured that a common biblical language developed throughout the Methodist movement. Adherents were strictly devoted to prayer, Bible study, taking communion every week, fasting regularly, and abstaining from luxury. They regularly visited the sick, the poor, and the imprisoned - the kinds of people who were attracted to Methodism or evangelical religion more generally. They tended to be predominantly, though not exclusively, from the middling orders, although there was always a sprinkling from the "upper echelons of society, and some drawn from the lower orders, but the majority were merchants, shopkeepers, booksellers or craftsmen". In rural areas small farmers and industrious labourers tended to dominate the membership. Women made up at least and sometimes considerably more than half of the total membership. In general, members were literate, tending to be eager to learn, and they were industrious and frugal, all qualities which predisposed them to the self-improving undercurrent of the Methodist message.

The social and political impact of Methodism

So too, did the considerable religious impact of Methodism have upon the emerging Labour movement in the Nineteenth Century. Methodism’s “roots lay in three areas in particular: the French revolutionary spirit of ‘liberty, fraternity and equality’, early Owenite socialism (cooperation and state ownership) and John Wesley’s Methodist religion of the poor.”

To carry on the campaigns to help the needy and the poor, every Methodist society was duty-bound to contribute a penny a week for working with the disadvantaged, campaigning for better conditions of work, protesting against slavery, prison brutality, supporting universal suffrage, and educating the poor.

Methodists were particularly active in the early stages of the Sunday School movement and accounted for thirty percent of all Sunday School scholars by 1851. By giving lay members (not professionally qualified) opportunities to accept added responsibility, Methodists learned managerial skills and took advantage of speaking opportunities.

They also utilised the established three-tiered organisational system of Wesleyan Methodism: national conferences, district circuits and local chapels. Interestingly, most trade unions adopted this pattern in the 1860s, and still organise themseleves on this basis even traditionally describing their branches as "chapels". This social and political impact of Methodism eventually became the norm in conformist practice as the "Established Church" and other denominations also contributed to the development of the labour movement.

The Methodism of John House

The John House we have identified as "the senior" was born in 1785 into a craftsman's family. He spent his formative years at a time of ever widening expansion of the Methodist movement. He almost perfectly fitted the description of the typical Methodist of his time and indeed of the century and more that followed. Indeed history records the active participation of other Wheelwrights in the movement. Methodism's ideas of social justice as well as its theological beliefs and practices must have appealed to John House and to his children who were no doubt raised in the beliefs and practices of their father.

No doubt all of these circumstances contributed to the substantial donation by John House to the Wesleyan Methodist movement sometime in the early 1800s.

Near the beginning of this story we passed quickly over the building which stood on the corner of Cheapside Lane and Ashmead Lane in the small community of cottages which had John House wheelwright yard at its centre. It was said, in the Tithe awards of 1843 to be in the ownership of the Trustees of the British School. The Schoolmaster was one John Cheesman, himself shown in the 1841 census as an occupier of one of the cottages and a witness to the Will of John House senior in January 1837.

The relatively little known "British Schools" were schools for poor children established by non-conformists to parallel the schools being established by the Anglican Church. Recalling also the Bowyer Charity School for poor children endowed by Sir William Bowyer in 1721, the existence of the British School in Cheapside Lane demonstrates a proud and longstanding commitment to education in the Denham community.

Few records have so far been located to describe what happened to the Methodist Church after John House's death in 1837. Presumably the directions contained in his Will were followed. We do however have a fascinating entry in the Census of Religious Worship carried out in 1851. It tells us that the Wesleyan Chapel in Denham was a separate and entire building used exclusively as a place of worship i.e. no longer someone's house. In the box marked "When erected" the Chapel Steward has entered 1819, but he may have offered that not as the date the chapel was built but rather as the date when John House had it first licensed. Its Sunday School attracted 30 attendees on Sunday afternoons and its evening services on Sundays only had a congregation of just 12, not many, if any, more than the occupants of the surrounding cottages together forming Denham's early Methodist community. The Church Steward signatory to the census form was one William Pratt, a gardener and, according to the 1841 census, the then next door neighbour of John House junior - though John himself had by 1851 moved to a more substantial property in Vine Street, Uxbridge amongst other business people and professionals. William is no doubt also the William named as "Platt" in the Tithe Award of 1843.

Methodism into the 20th century

A cursory review of newspaper articles and Methodist census reports show rapid growth of UK Methodism in the middle of the 19th century, and even greater when informal affiliations to Methodism were included. Nearly 1.5 million supporters were claimed in 1851. Methodism grew particularly rapidly in the old mill towns of Yorkshire and Lancashire, where the preachers stressed that in the eyes of God, the working classes were equal to the upper classes. This was a message that appealed to ambitious middle class families, less so of course to England's landed gentry.

Methodist membership declined in the early 1900s. On July 20, 1946, The Lancashire Daily Post reported the “Methodist Church Slowly Dying Out”. A similar message was delivered by the Rev. V. Proctor to the Methodist Conference in London, but the then Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Geoffrey Fisher offered reconciliation with the Anglican Church saying: “The relationship between us is very close. Even if you think of the Church of England as a rather fossilized parent of yours, it is still your parent, and if we think of you as a rather adolescent and awkward child, you are still our child.” This offer of reconciliation had been delivered for consideration. It was then rejected and reconciliation had then to wait until the mid-1990s when informal conversations between the Church of England and the Methodist denominations resumed, finally resulting in a covenant in 2002 that affirms their willingness to work together at a diocesan/district level in matters of evangelism and joint worship.

In Denham the old Methodist Church had survived. On March 26 1948 the Uxbridge and West Drayton Gazette carried a report from the Denham Methodist Church news: “The Church has recently been redecorated and has received a gift of hymn books from each of the other churches in the Circuit, in preparation for the re-commencement of evening services in the beginning of April. This Mission meeting is always a feature in the Circuit as the Denham Chapel is of such historic interest."

The January 1974 Denham Newspaper in its section “Around the Parish”, reported that five services were scheduled at the Methodist Church: four in the evening and communion one morning. A different clergy was named for each of the five services. The Women’s Fellowship meeting as well as a meeting of the Methodist Guild was scheduled, indicating an active congregation.

But by 2009 the building known as the Denham Methodist Church, Cheapside Lane had been closed to church services. It was then sold to a private buyer. Still the story and the decency of John House, his family, and the values of compassion for which he stood are still present in our community.

_____________________________________

Photo images

Portrait of John Wesley by Nathaniel Hone circa 1766 © National Portrait Gallery, London - www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw06699/John-Wesley?

Denham Wesleyan Chapel (final paragraph) cc-by-sa/2.0 - © Stefan Czapski - geograph.org.uk/p/3834546

Sources

www.thegenealogist.co.uk

1841 census image Ancestry.co.uk - 1841 England Census

South Bucks District Council, Denham Conservation Area Character Appraisal, September 2008

Last Will and Testament of John House, signed 24 September 1830. The National Archives’ reference Prob 11/1885/189

Portrait of John Wesley by Nathaniel Hone circa 1766 © National Portrait Gallery, London - www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw06699/John-Wesley?

Census of Religious Worship 1851 discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C17328253

Wikipedia

https://www.google.com/search?q=UK+Methodist+history+1700-1800&rlz=1C1CHBD_en-GBGB754GB754&oq=UK+Methodist+history+1700-1800&aqs=chrome..69i57j69i64.17699j1j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8 The Elect Methodists, by Jones, Schlenther and White provides clear theological differences.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toleration_Act_1688 David Ceri Jones, Boyd Stanley Schlenther, Eryn Mant White, The Elect Methodists, 2016, Cardiff, University of Wales Press

Nigel Scotland, Methodism and the English Labour Movement 1800-1906, Anvil Volume 14, No. 1, 1997.

Ann Collins who attended and enjoyed evening services at the Methodist Church on Cheapside Lane.

Comments